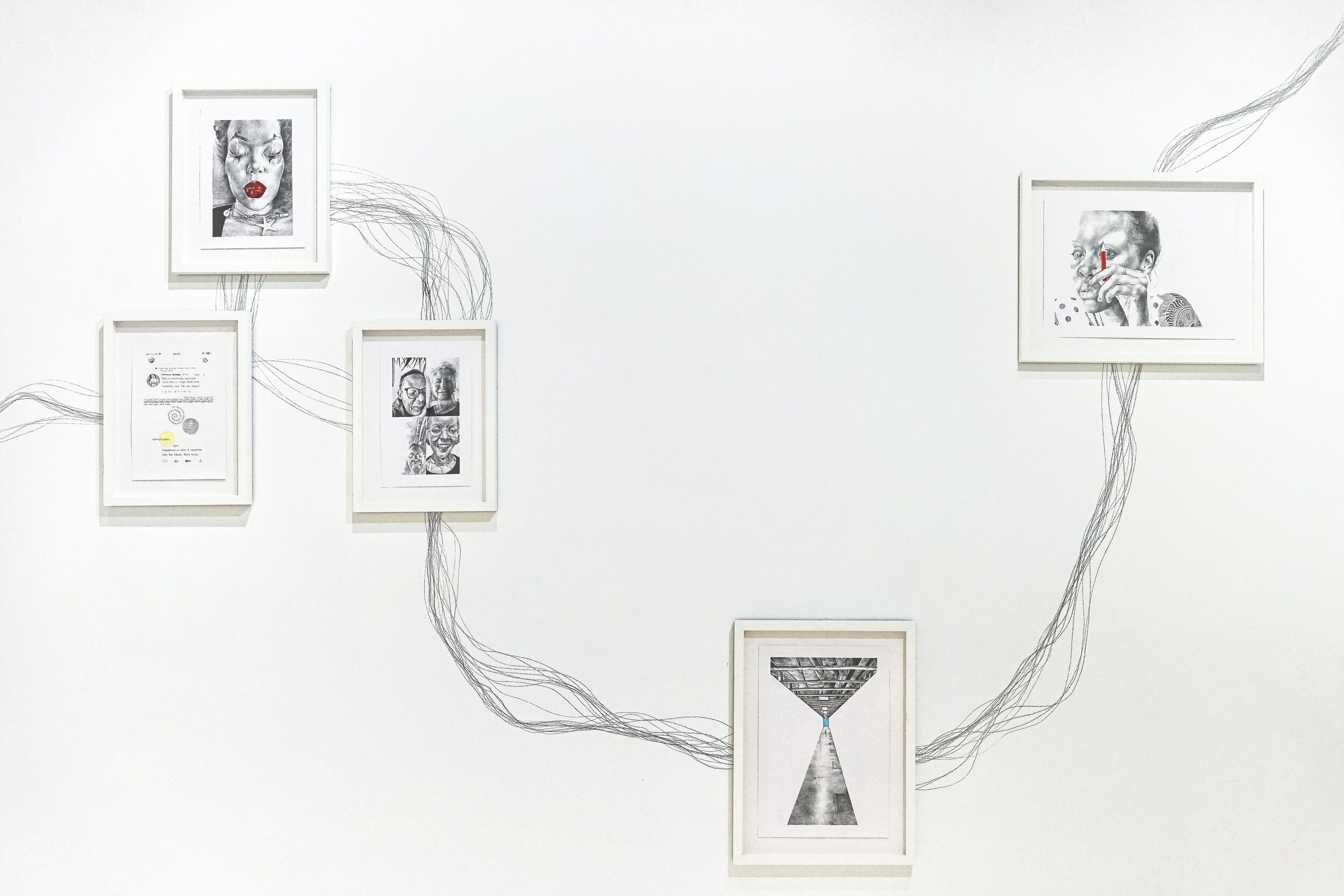

Still Life: A Taxonomy of Being

A capsule of drawings by Phoebe Boswell (Kenya/UK) made during the UK's third national lockdown.

Essay by Emma Chubb, Ph.D. Curator of Contemporary Art, Smith College Museum of Art

May 5, 2021 - June 12, 2021

Opening reception on May 5, 6-8pm. Groups under 8 are welcome.

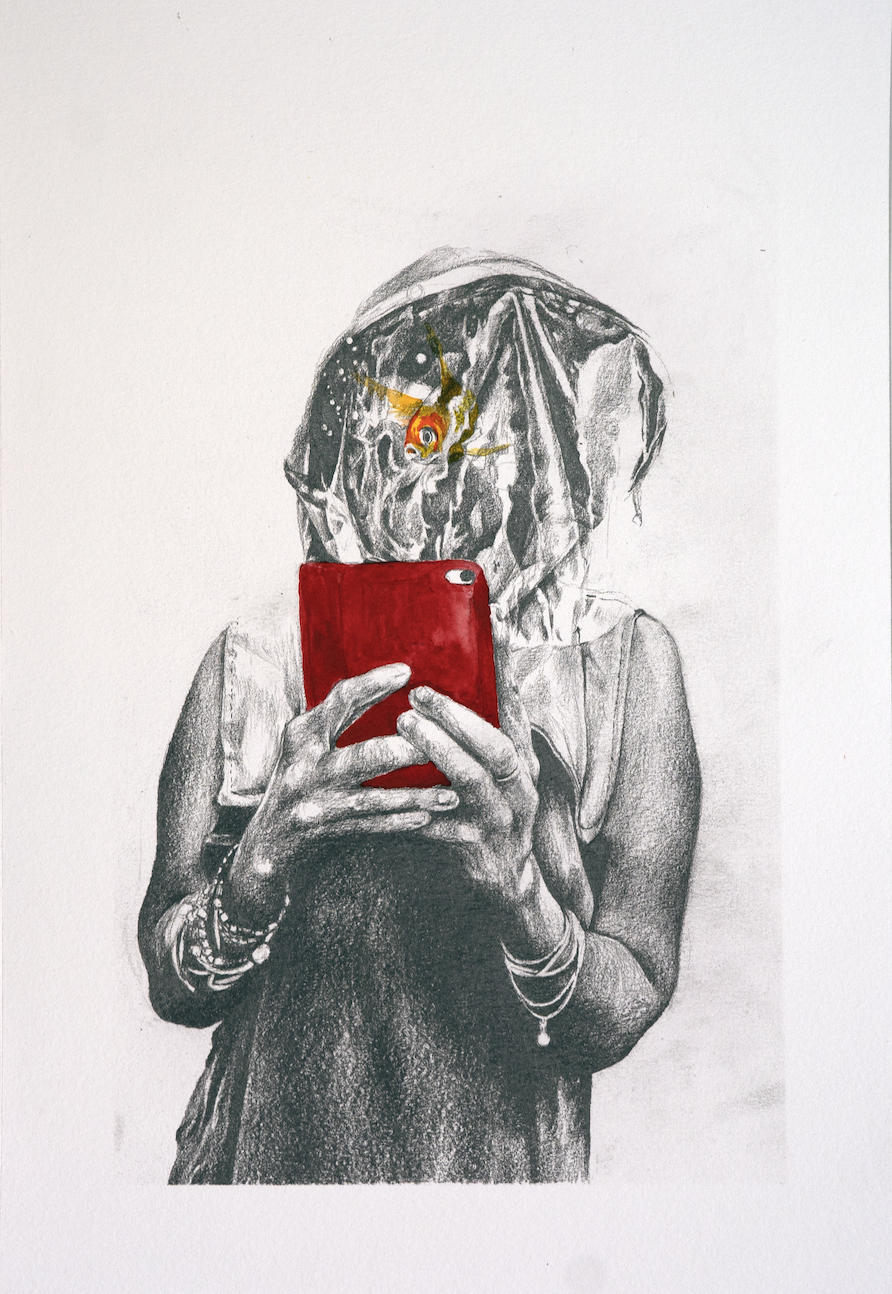

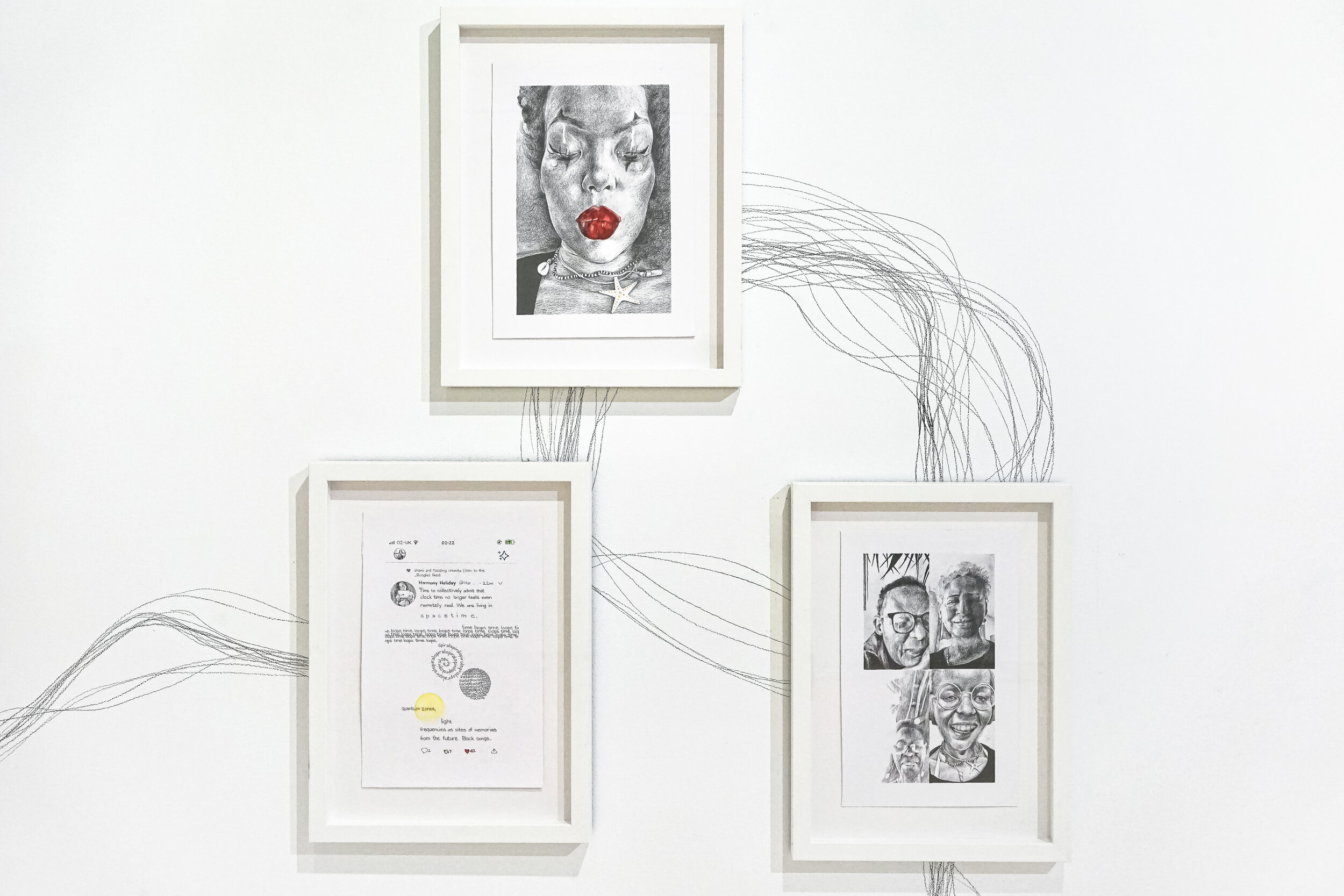

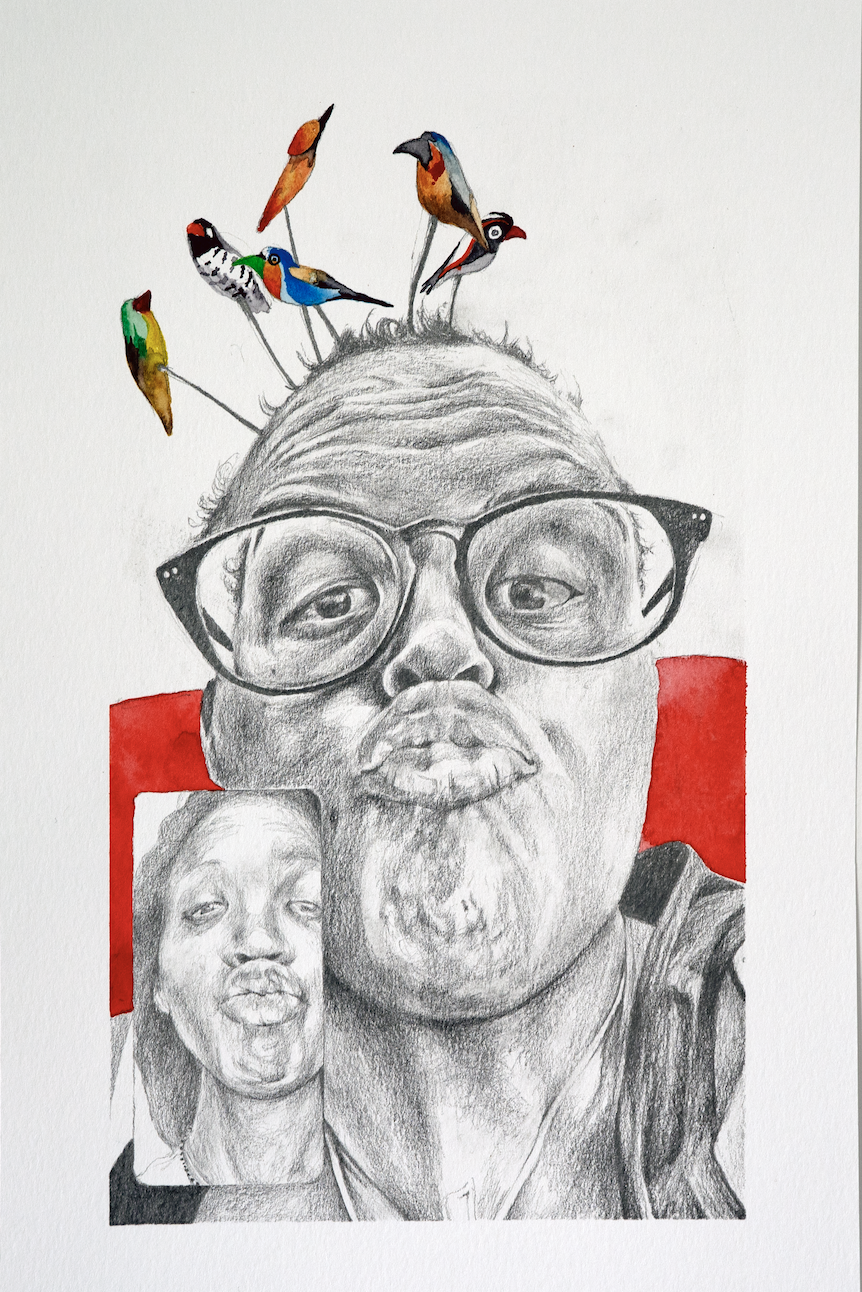

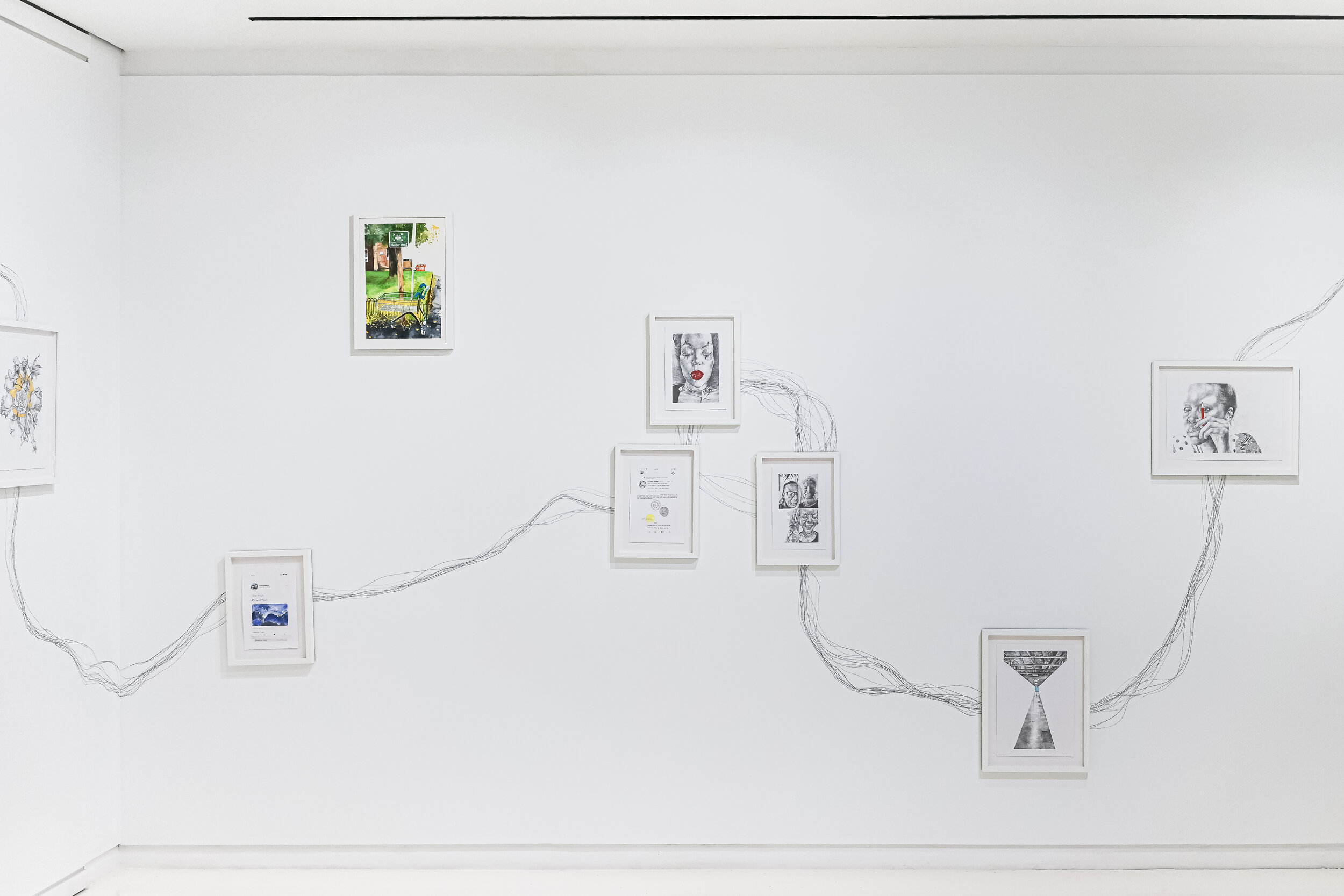

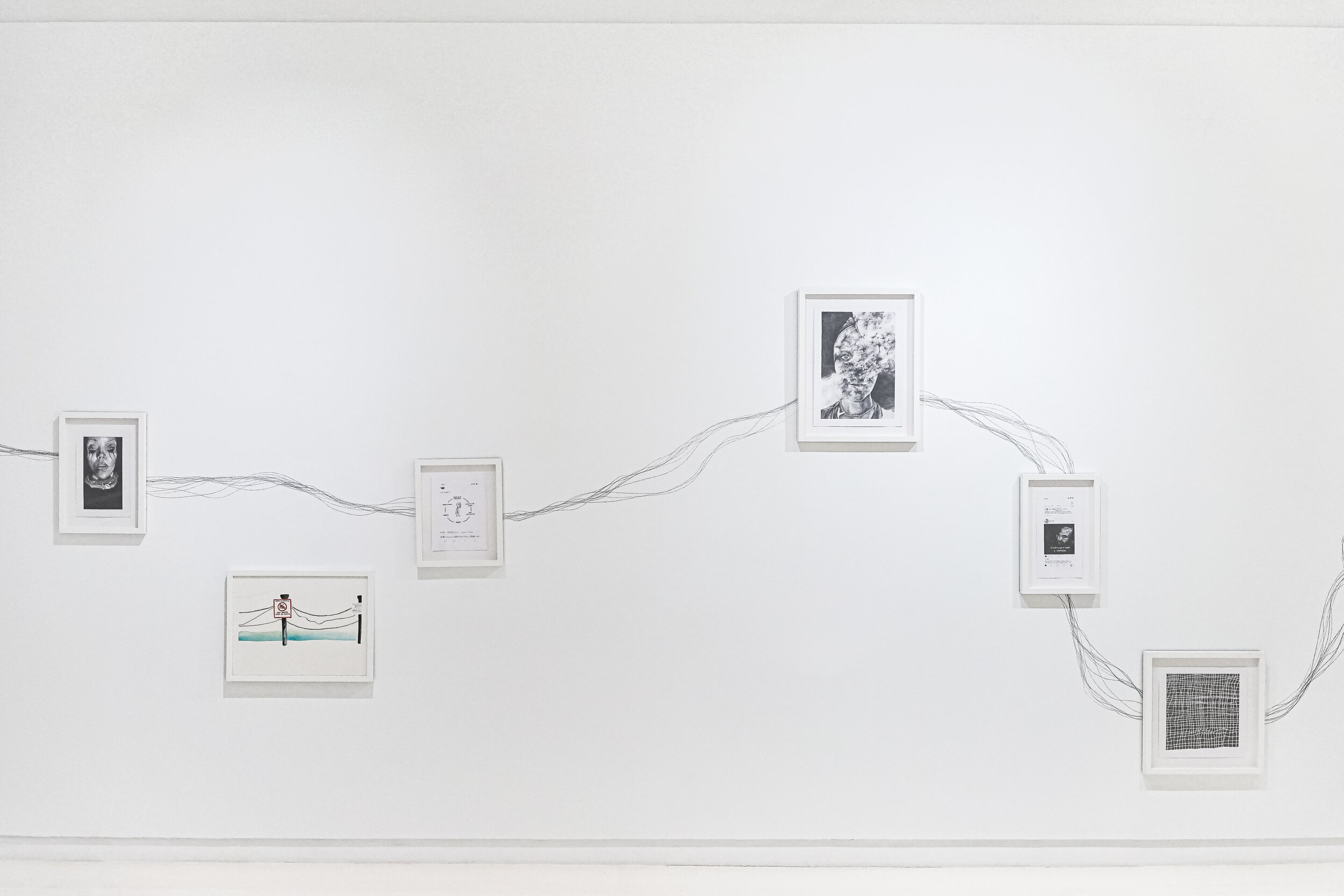

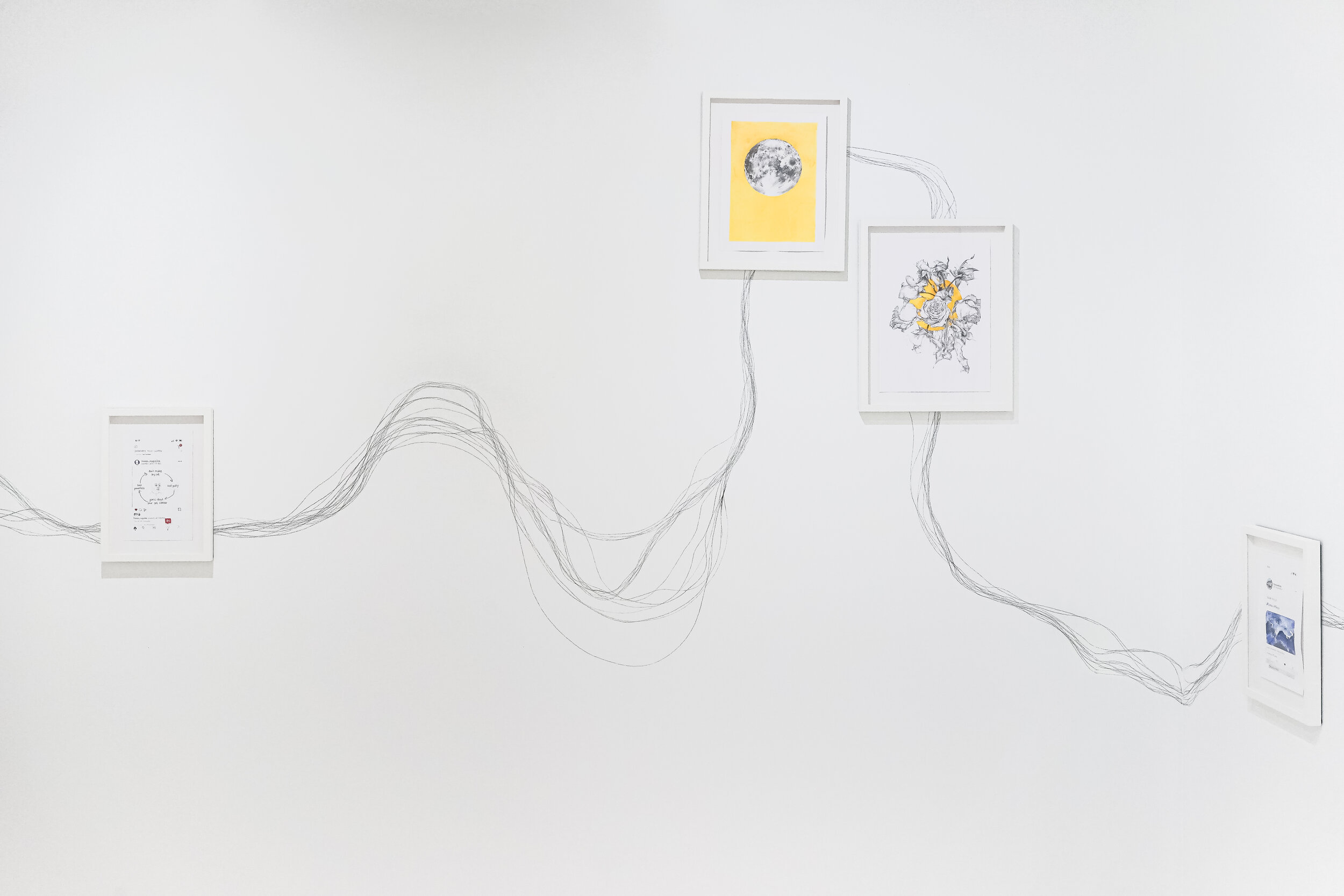

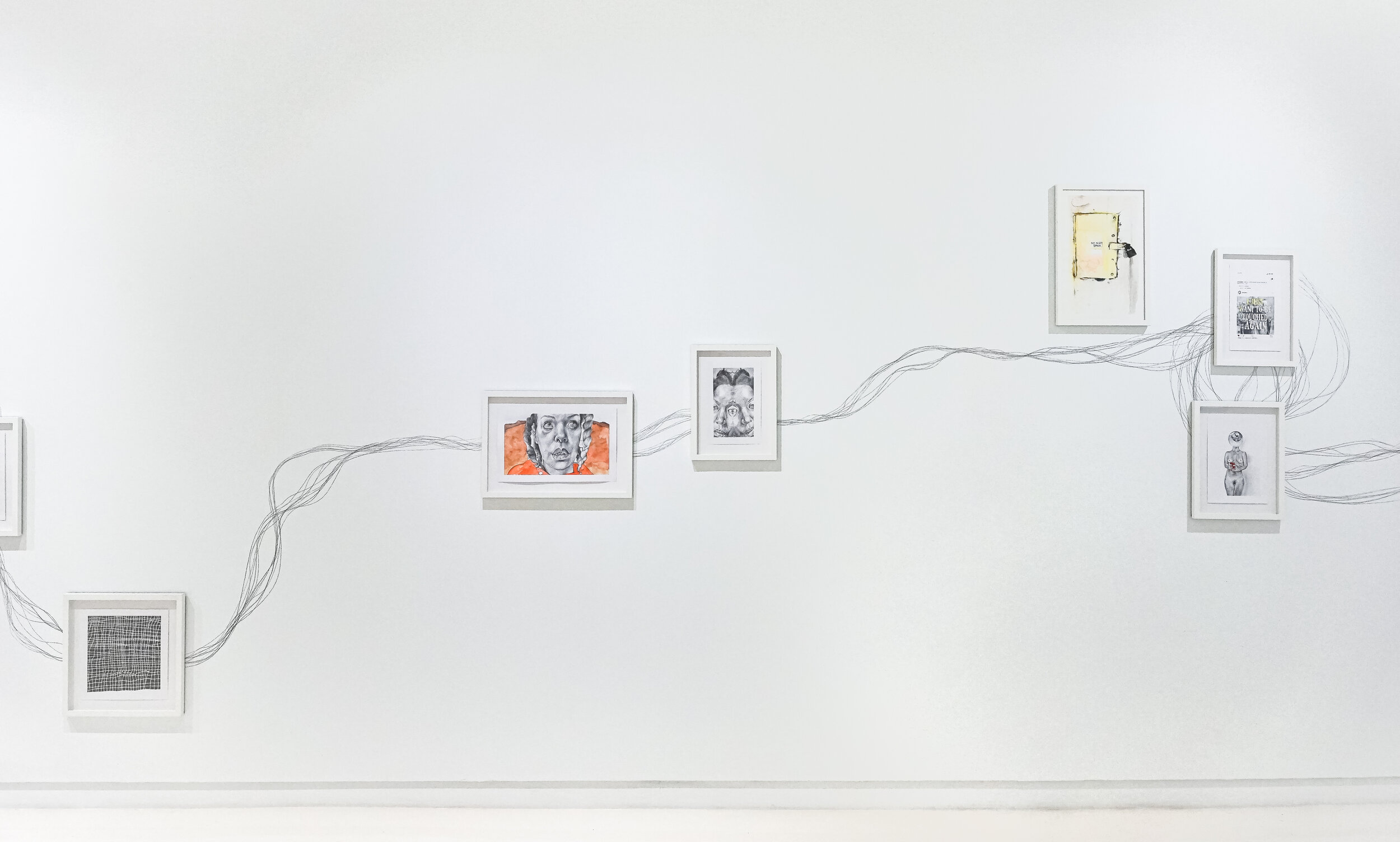

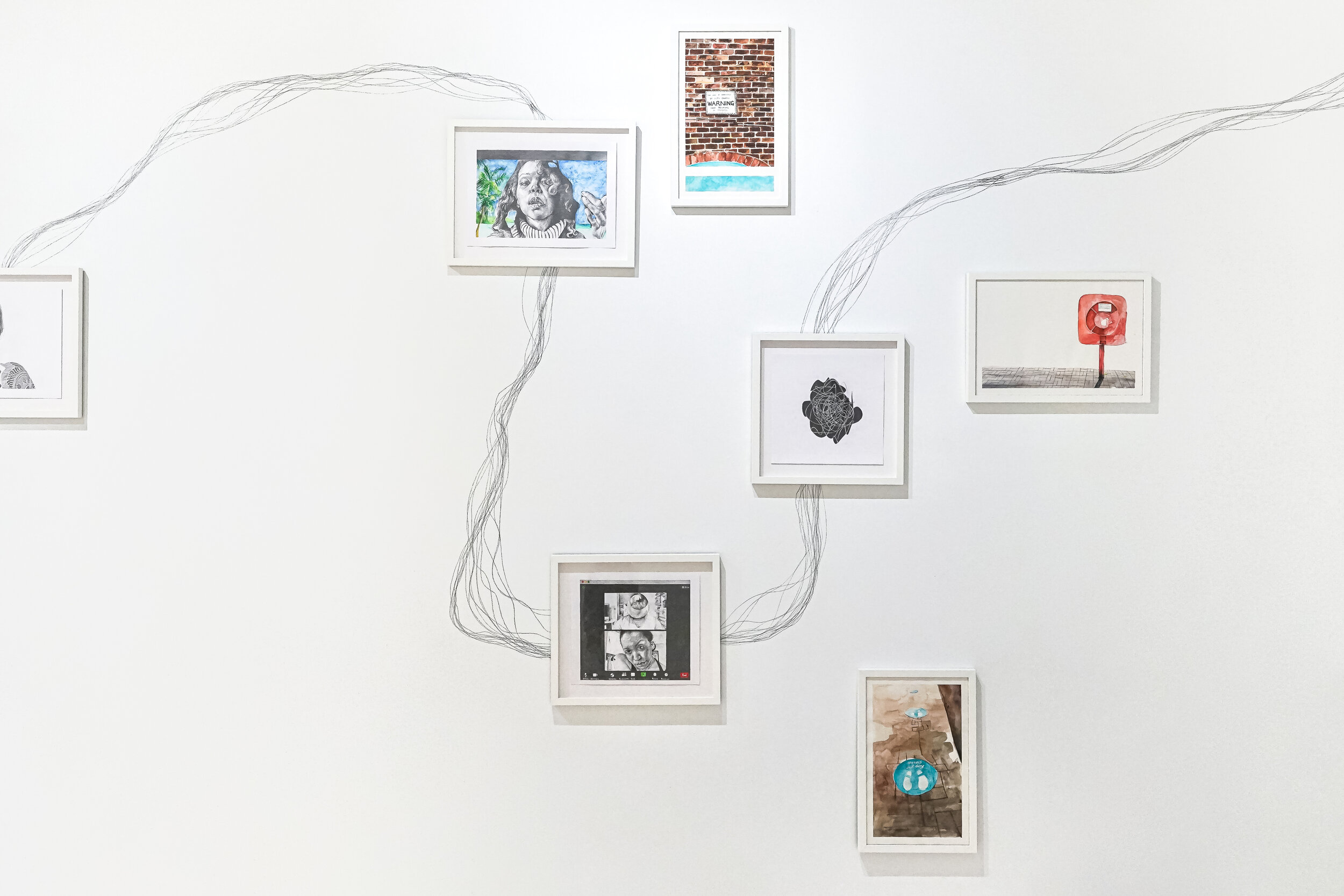

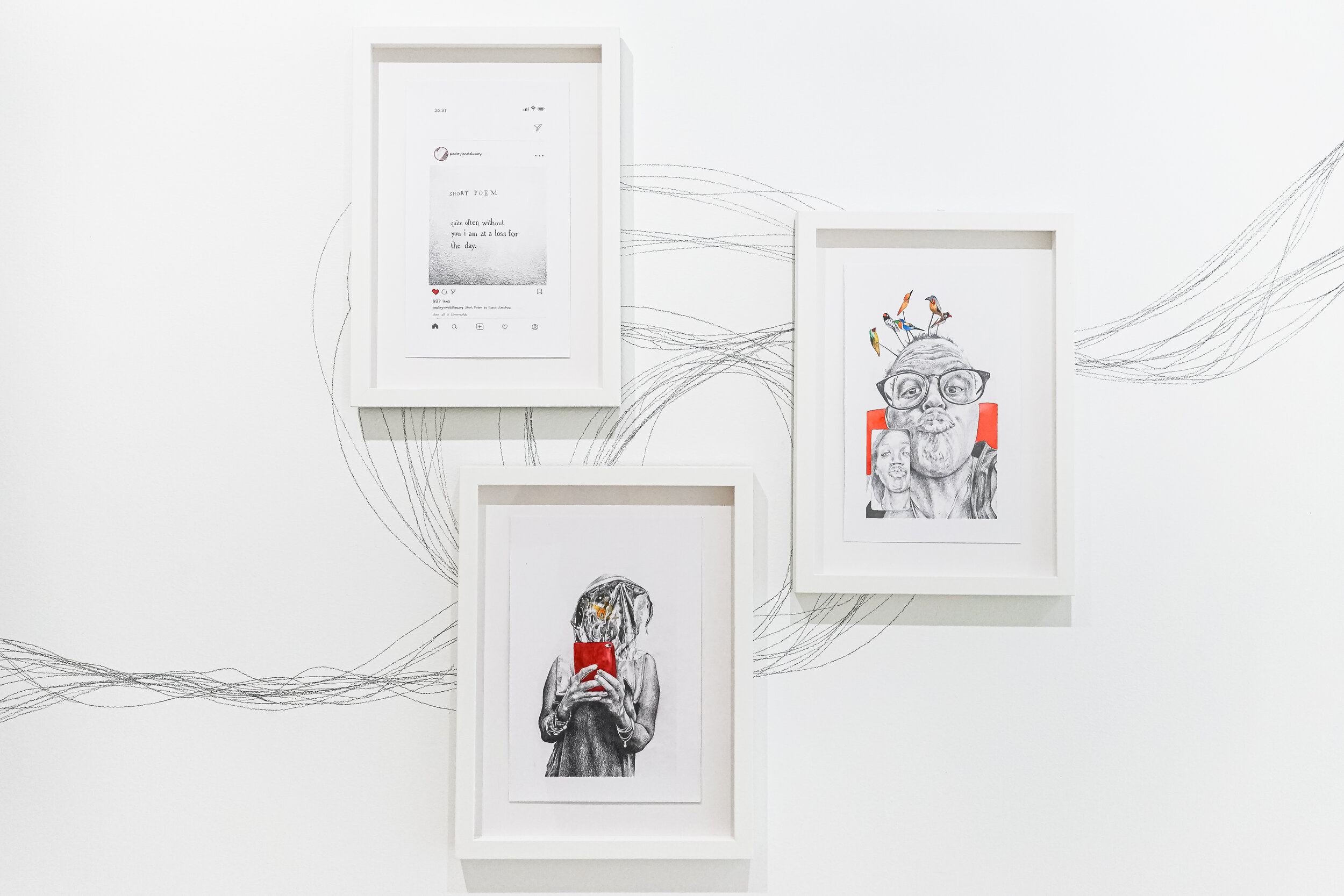

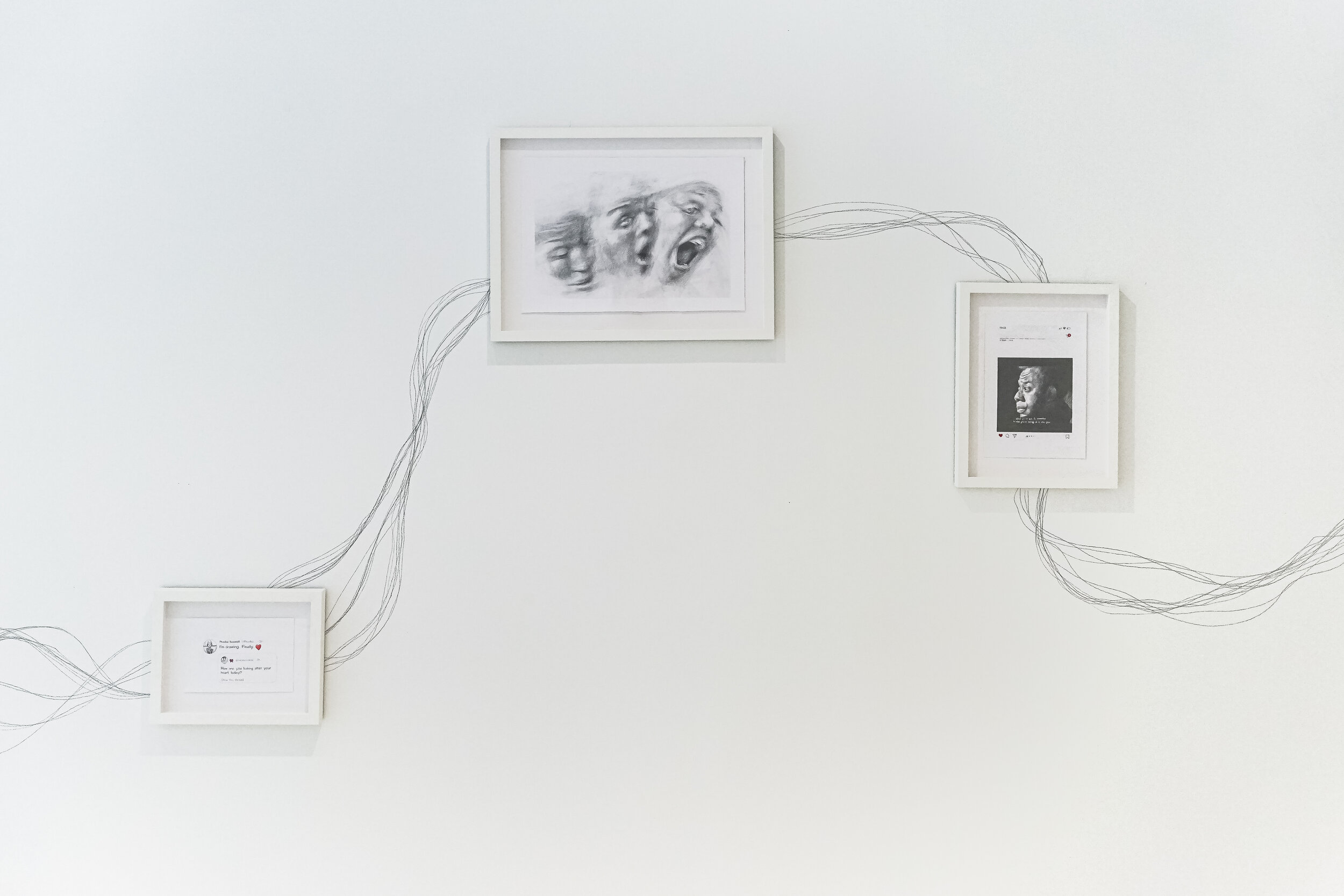

Sapar Contemporary announces Still Life: A Taxonomy of Being, the gallery’s second solo exhibition of work by Phoebe Boswell. The exhibition features 49 drawings, watercolors, and pastels created between December 2020 and April 2021, while Boswell was sequestered at home during the UK’s third government-mandated lockdown. The artworks and the sound of Boswell breathing fill the gallery, encapsulating a time in which breath became perilous and, for many, devices functioned as the primary mediators of being and belonging.

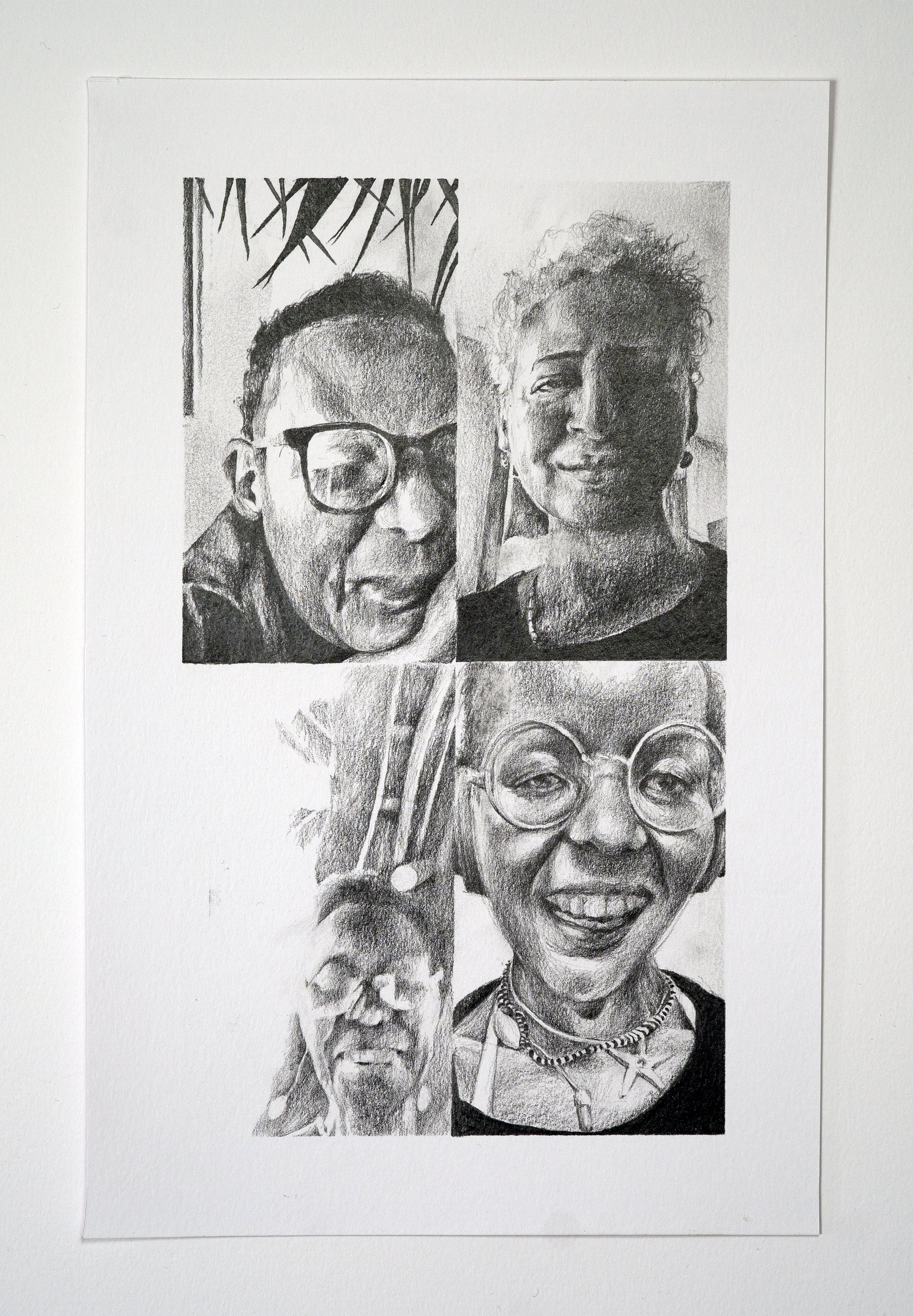

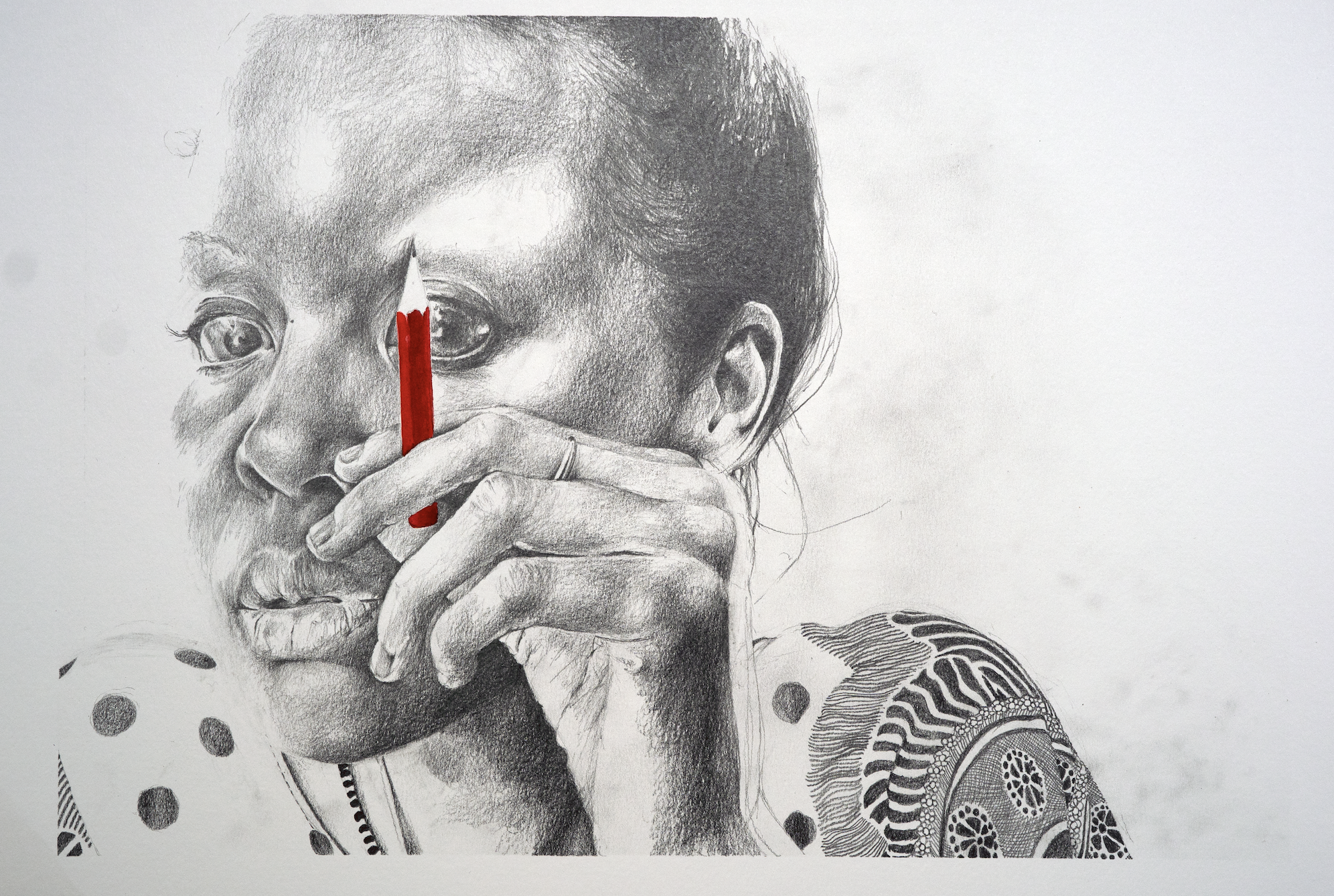

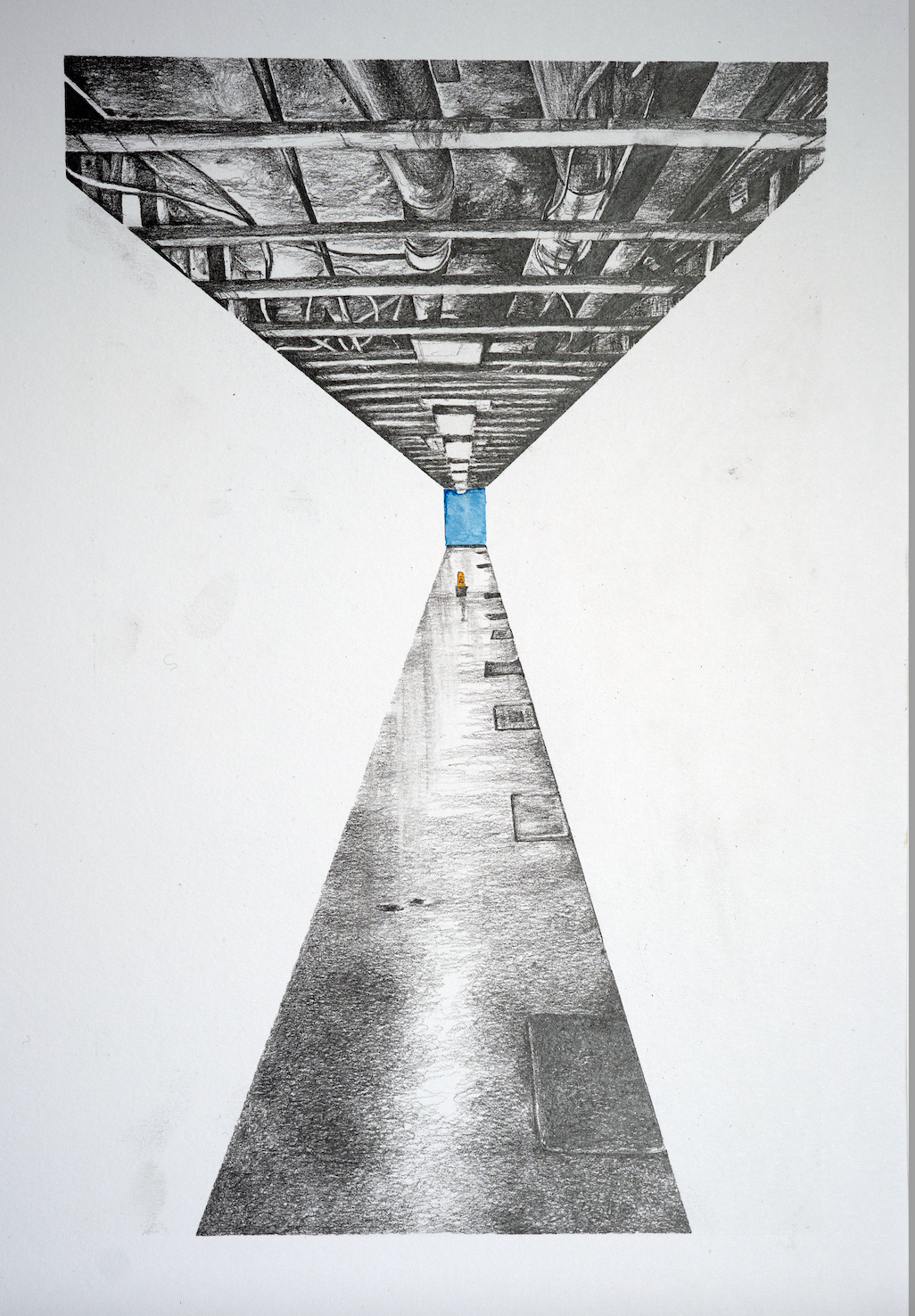

Much of Boswell’s work starts from the belief that “the most personal things are usually the most universal.” This understanding of the personal as always already implicated with the world outside of oneself echoes earlier generations of feminist artists like Adrian Piper, Sonia Boyce, Claudette Johnson, or Martha Rosler. They, too, make formally rigorous and conceptually rich artworks that mine everyday life and personal experiences to imagine liberating ways—or taxonomies—of being (1). Boswell does so in drawing, a medium in which she excels and whose limits and possibilities she pushes so expertly. Here, the personal and the everyday resound, transformed from diaristic snapshots of Boswell’s life in lockdown and extending the themes of portraiture, technology, grief, memory, and resilience that she has long explored. There are self-portraits that began as selfies, with filters and virtual backgrounds suggesting who or where one might rather be. Some drawings reference screenshots and memes pulled from Twitter or Instagram, as if mid-scroll, all related to people or posts that made Boswell feel less alone. Others communicate the solitude of lockdown: a long and empty corridor, cut flowers that have begun to droop, the sky seen from Boswell’s apartment window.

Drawing is time consuming and private, physical and direct. It is noticeably absent from the many activities listed in Boswell’s “Notes on a pandemic,” posted on Instagram on March 30, 2020, four days after the UK’s first lockdown began. Opening with the now rote chorus of “Mask Up. Wash hands. Stay home,” Boswell’s words, all in a fast-moving present imperative, convey the bewilderment and anxiety about what to do and how to protect, soothe, and care for oneself and for one’s communities. It concludes: “Go to the window and let the sun kiss your face. Stroke yourself. Stimulate your senses. Ululate. Be still. Breathe.”

At the outset of the first lockdown, as the UK issued government mandate for all to Stay At Home, Boswell learned that she had been identified as someone at severe risk from COVID-19 and placed on the “shielding” list . It was only during the third lockdown that she returned to drawing daily. For four months, she drew consistently and prolifically, mostly at a table in her apartment, in part as a way to pass the time and in part because drawing provided a means of survival and an expression of care for the self and for others. In this way, the works function as “time documents,” to borrow artist Mounira Al Solh’s evocative description of her project, I Strongly Believe in Our Right to Be Frivolous (2012-7), also made during and about a prolonged period of crisis (2). Boswell drew on her own and while on Zoom with friends and fellow artists, each working in silence. Drawing offered a way to reflect on the new forms of collective and interior imagining that began to coalesce during the pandemic, thanks in part to how online platforms like Zoom have expanded access to knowledge sharing. Boswell attended online lectures and she read, a lot: Octavia Butler, Dionne Brand, Édouard Glissant, Lola Olufemi, Zadie Smith, Christina Sharpe, Rinaldo Walcott, Mariame Kaba, Saidiya Hartman, Keguro Macharia. The scale of the resulting works indexes the experience of making art in a lockdown, when Boswell had very limited access to her studio and almost no access to other people except via a device and an internet connection. Because nearly every drawing is in some way mediated by the digital, the taxonomy of being to which Still Life gives form centers the pandemic’s acceleration of our dependence on these technologies for human interaction.

Boswell’s taxonomy also includes the street signs that serve as the main protagonists of her few outdoor scenes. Rendered in watercolor, Boswell’s first time using this medium, they reference her riverside walks between home and studio, the only time she left home during lockdown. Although their installation likely predates the pandemic, the signs’ once banal and bureaucratic language—Warning! Ever Present Danger! End!—takes on new, more sinister meanings in a year when vulnerability to sudden death and state surveillance grew harder to ignore.

Of course, vulnerability to sudden death is not new nor has it been evenly experienced during the pandemic. Structures both social and governmental have always shaped whose life is valued and who is made vulnerable around the globe. As Dionne Brand wrote in July 2020, the pandemic has “expose[d] even further the endoskeleton of the world.” (3) Exposed, but also re-entrenched, as places like the US and UK hoard vaccines and reproduce deep-seated racist and colonialist tropes in reporting on the pandemic outside of the so-called West (4). How, then, as Boswell put it when we spoke, to make art in ways that witness these realities, that draw credence to grief while resisting its commodification? Can this refusal be respected? Should the drawings leave their site of creation and enter the public sphere?

The new forms of sociability, the longing for touch, the boredom that begets playing with filters or scrolling social media, the raw fear of one’s own death and that of those we love without the possibility of grieving them in the ways we know how, the anger—also raw—at government negligence and murderous intent, articulated along the same monstrous lines as before. A capsule, a taxonomy of being, a world building, a network of care. Consider what we carry into the future. Imagine differently how the pieces can fit together. Acknowledge that the individual cannot be separated from the collective, the personal from the universal, my breath from yours. Be still. Breathe.

The author is grateful to Phoebe Boswell for her generosity in sharing her work and insights into it during the writing of this essay.

1. For example, Piper’s Mythic Being (1973-5); Boyce’s The Audition (1997); Johnson’s Untitled (1972); Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975). See also Adrian Piper, “Xenophobia and the Indexical Present I: Essay” (1989) and “Xenophobia and the Indexical Present II: Lecture” (1992), in Out of Order, Out of Sight: Volume I, Selected Writings in Meta-Art, 1968-1992 (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996), 245-251; 255-273.

2. I Strongly Believe is comprised of portraits of those who emigrated from the Middle East and North Africa following the uprisings of 2011 and the Syrian War. See Hendrik Folkerts, “Mounira Al Solh,” documenta 14: Daybook (2017). Available online: https://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/13500/mounira-al-solh.

3. Dionne Brand, “On narrative, reckoning, and the calculus of living and dying,” Toronto Star, Saturday, July 4, 2020. Available online: https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/books/2020/07/04/dionne-brand-on-narrative-reckoning-and-the-calculus-of-living-and-dying.html.

4. See Helen Tilley, “COVID-19 across Africa: Colonial Hangovers, Racial Hierarchies, and Medical Histories,” Journal of West African History, 6:2 (Fall 2020), 155-179.

Phoebe Boswell (Kenya). Underpinned by a transient and diasporic consciousness, Phoebe Boswell’s practice speaks from the porous space between here and there. She works intuitively across media, centering drawing but spanning animation, sound, video, writing, interactivity, performance and chorality. This tends to culminate in layered installations, which affect and are affected by the environments they occupy, by time, the serendipity of loops, and the presence of the audience. Aesthetics of figuration and representation through the radical imaginary of Black feminisms become tools for contemplating the body as world, worldmaking, rather than merely as object to be gazed at. Artmaking becomes a political act of service to community, where labour-intensive drawing practices, immersive technologies, and calls for collective participation denote a commitment of care for how we see ourselves and each other; how we grieve, how we love, how we rest, how we heal, how we protest, how we remember the past in order to imagine the future.

Boswell (Kenya/UK) currently lives/works in London, and her work has been exhibited globally, including Autograph; Sundance Film Festivals, Göteborg International Biennial for Contemporary Art 2015, and Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement 2016. She received the Future Generation Art Prize's Special Prize in 2017 and recently unveiled a large-scale public moving image work 'PLATFORM' as part of the Fonds cantonal d'art contemporain in Geneva. Boswell was the Bridget Riley Drawing Fellow at the British School of Rome in 2019, is a current recipient of the Paul Hamlyn Award for Artists, a Ford Foundation Fellow, will this year present newly commissioned works at Prospect P5 in New Orleans and Hache Noce in Oaxaca, and has solo exhibitions at New Art Exchange, Nottingham and Sapar Contemporary, New York both opening in May (according to Covid-19 guidelines)

Emma Chubb, PhD, is the inaugural Charlotte Feng Ford ’83 Curator of Contemporary Art at the Smith College Museum of Art (SCMA). Chubb is the curator of Amanda Williams: An Imposing Number of Times (2020-22), a site-specific commission at Smith, and a future retrospective on the work of Younes Rahmoun, a project supported by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Her essays on the representation of migration in contemporary art have been published in Art Journal and Journal of Arabic Literature. She earned her BA in art history and French from Haverford College and PhD in art history with a certificate in Middle East and North African studies from Northwestern University.