Mongol Zurag: The Art of Everyday

Uurintuya Dagvasambuu and Baasanjav Choijiljav

October 13, 2019 - November 13, 2019

Curated by Uranchimeg Tsultemin Ph.D., Edgar and Dorothy Fehnel Chair of International Studies and Assistant Professor of Asian Art at Herron School of Art and Design, Indiana University

Sapar Contemporary is delighted to present the first exhibition dedicated to Mongol Zurag art in New York City featuring two of the most prominent representatives of this style, D. Uurintuya and Ch. Baasanjav. Mongolian traditional style of painting rooted in a Buddhist pictorial tradition is known as Mongol Zurag (literally: Mongolian picture).[1]This tradition was instrumental in maintaining the cultural identity for Mongolian artists during the period of socialism in the twentieth-century. It was largely suppressed prior to 1990, when Mongolia opened its doors to the world after seven decades of socialist regime as Asia’s new democratic, multi-party country. Mongol Zurag subsequently was further developed in this century being boosted by contemporary changes of Mongolia’s economy and politics.

Mongolia, a landlocked country sandwiched between People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation, is an ancient country with millennia-old cultural traditions. In the past century, when Mongolia was one of the Soviet allies as part of Eastern socialist bloc, the culture of European oil painting and art institutions were introduced to Mongolia from Moscow and became dominant with political aims to silence and limit the awareness of the past and of the traditions. The knowledge of history, traditional writing scripts, and traditional culture was heavily suppressed with the introduction of Cyrillic alphabet and the Soviet-style art of Socialist Realism and architecture. The city-monastery Urga, which was the main seat of the Mongol reincarnate rulers and the center of Buddhist culture until 1924, fell victim to socialist purges and was rebuilt as Ulaanbaatar (“Red Hero”) in 1940s.[1]Over a thousand of Buddhist monasteries that contained numerous arts and crafts were all, but two (Gandan and Erdene-Zuu), destroyed and many Buddhist monks were massacred by the revolutionaries. Those who survived, disrobed and became civilians, and some became artists. In this century-long transformative Soviet campaign, Mongol Zurag was the key element that was intentionally developed for sustaining the Mongolian identity.

The questioning of national identity that aims to distinguish itself in the radically transforming society under the foreign influence was not unique to Mongolia. The socio-political and cultural conditions that triggered the emergence and the development of Mongol Zurag are reminiscent of the similar motives that led to the creation of guohua (“Chinese painting”) and nihonga (“Japanese painting”) in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.[2]In these countries, the question of what constitutes the “national painting” and the “traditional style” became central[3]due to modernizing changes and, in Mongolian case, due to aggressive Sovietization campaigns carried out throughout Mongolia. Certain twentieth-century artists, such as Nyam-Osoryn Tsultem (1923-2001) and U. Yadamsuren (1905-1986) played an instrumental role in developing Mongol Zurag into a robust tradition, and in insisting on its inclusion in the curriculum of the state-run Institute of Fine Arts.[4] The two artists, Uurintuya and Baasanjav, are among the students who were trained in the class of Mongol Zurag in that Institute.

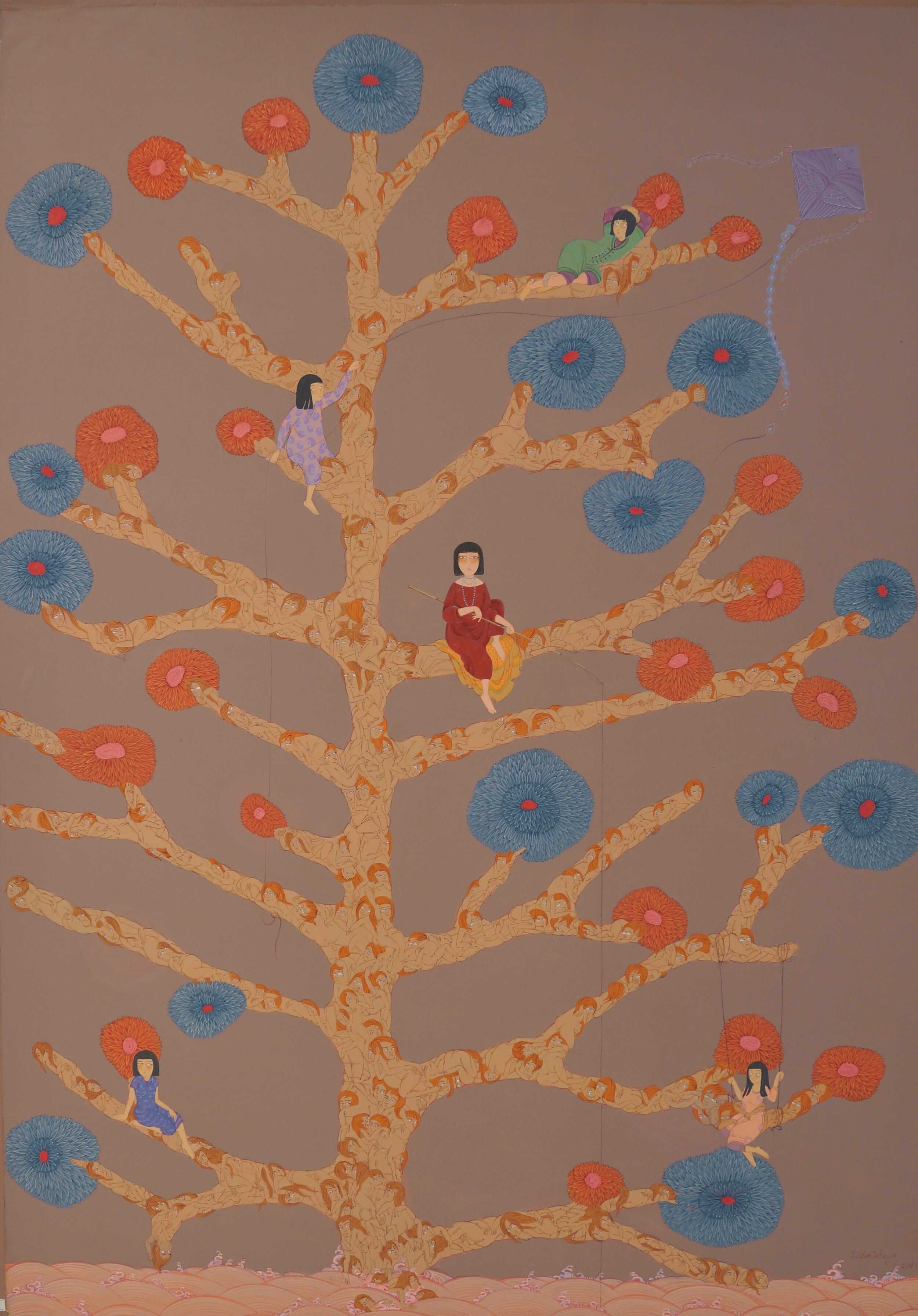

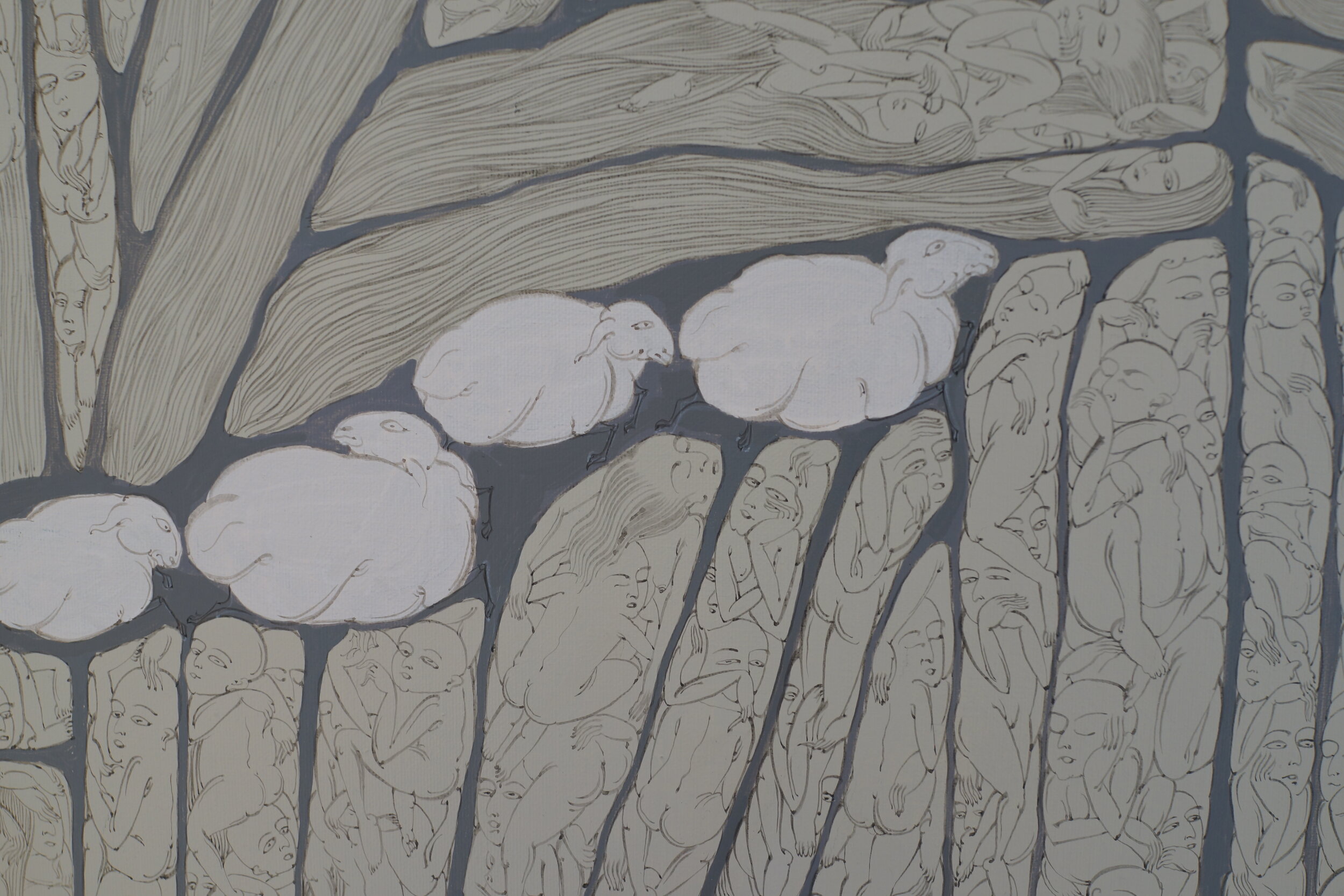

In historical masterpieces, such as One Day in Mongolia (ca. 1912), Mongol Zurag is applied to depict the wit, humor and grotesquerie of Mongolian quotidian through a narrative composition construed of vignettes and scenes.[5]Motifs used in Buddhist thangka paintings, such as exaggerated forms of fire flames, decorative elements and patterns of Buddhist landscapes and of accompanying material culture now being re-examined by new artists without any particular contextual associations. In contemporary developments seen in both artists’ diverse works, Mongol Zurag has taken ornamental linear forms that sensualize the dynamics of urban culture and incessant movement, breath-fullness of landscape and nature, subtlety of visible and invisible realities, tangible and sensory spaces (Uurintuya’s The Sound of City, On the Road, I am the Space, etc.).

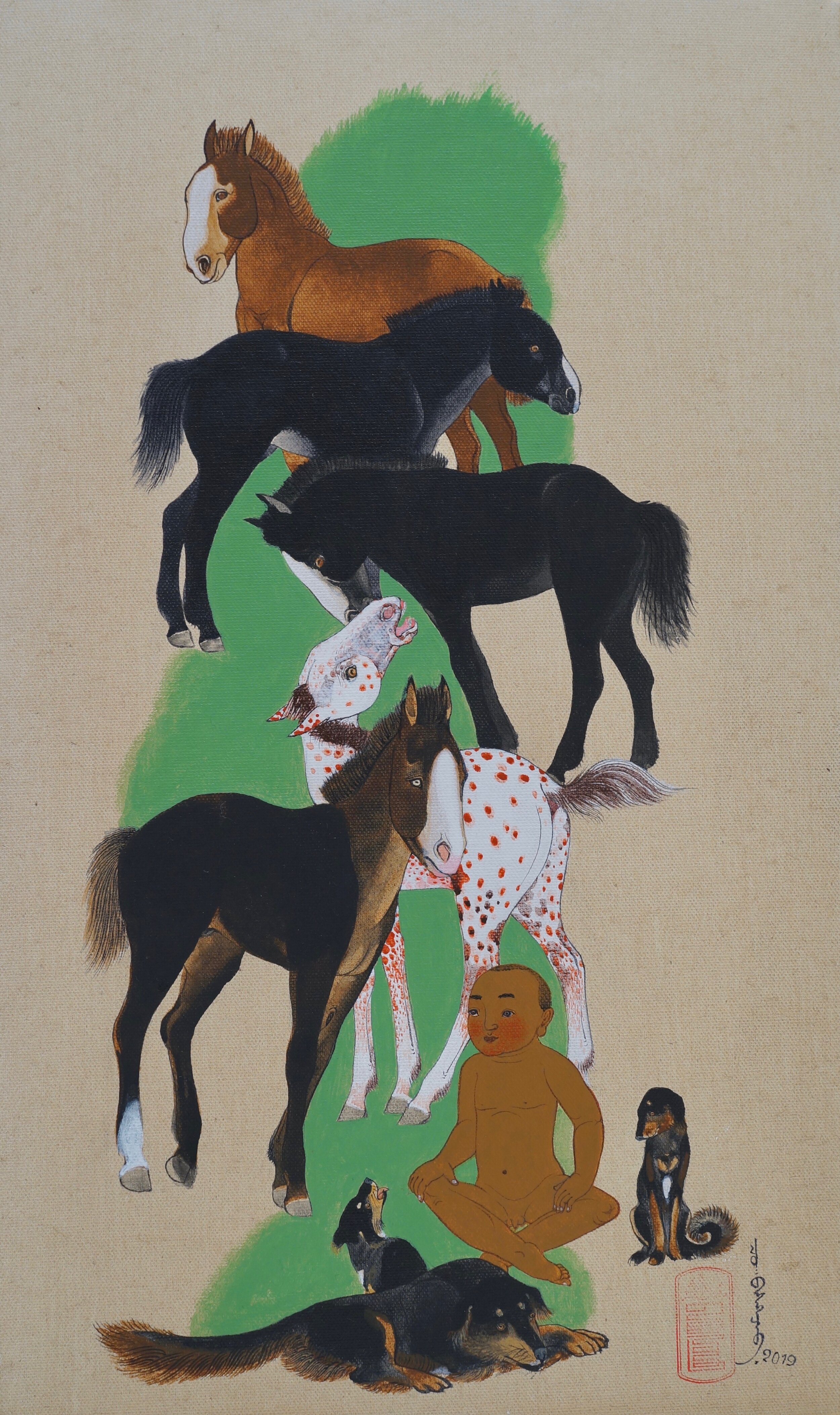

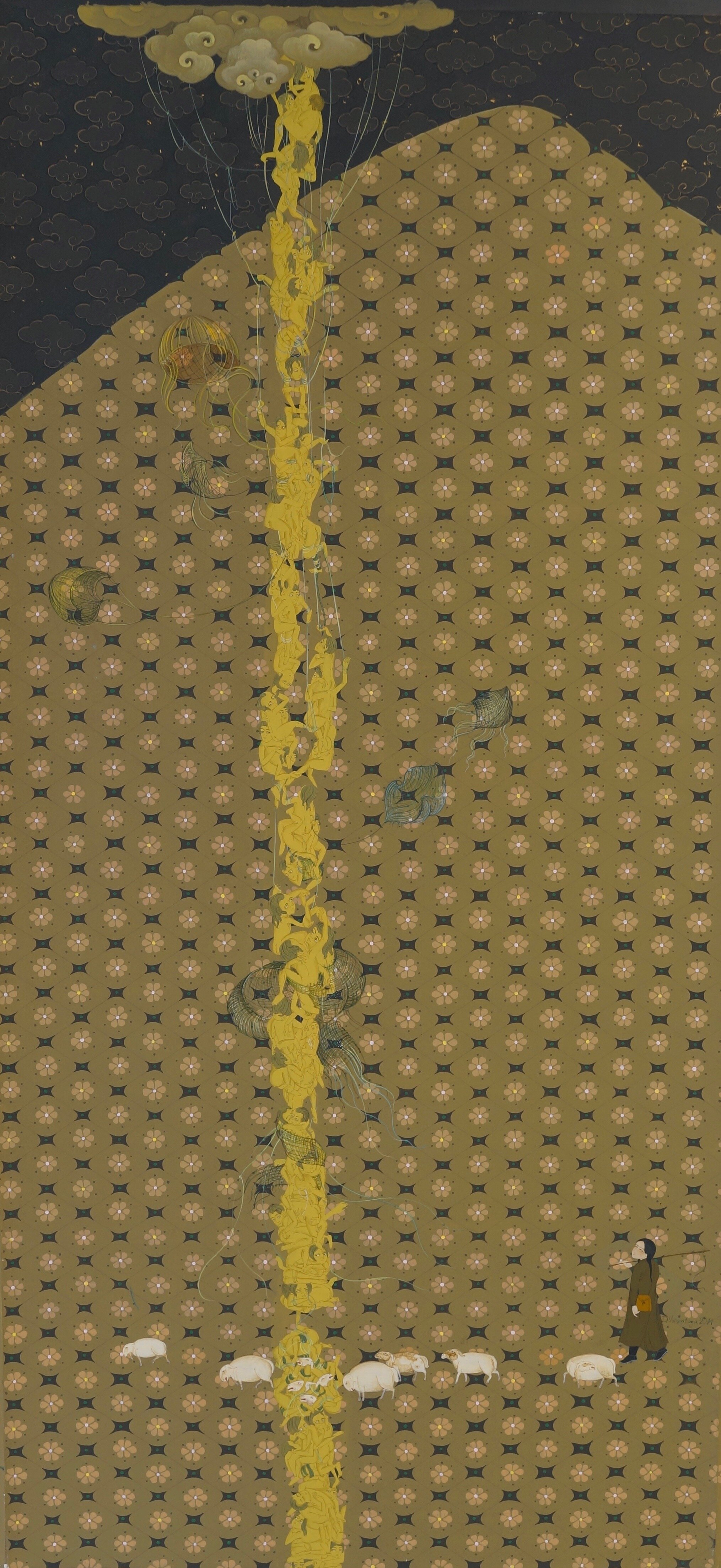

On the other hand, Baasanjav’s works explore Buddhist iconography and traditional motifs outside of their original context and their conventional use. He creates new forms inspired by wrathful visualizations of Buddhist deities (i.e. Palden Lhamo, Mahākāla, etc.) to place his Buddhist-like figures into compositions devoid of any religious meaning. Rather, he aims to hint at political chameleons and chauvinists, modern-day Nanas of destructive force who are pretentious and superficial, and have no core essence of humanity. In 2009, he had a breakthrough with his masterpiece The Taste of Money In-Between Clouds, which addressed the socio-political and environmental problems in the wake of the failing neoliberalism in Mongolia. In recent past, Fukuoka Asian Art Museum in Japan and Asa-Pacific Triennale in Queensland, Australia, organized Mongol Zurag exhibitions to recognize these artists’ innovative approach to Mongol Zurag. Uurintuya and Baasanjav continue to have a lasting impact in Mongolian contemporary art and artists.

- Uranchimeg Tsultemin, Ph.D

About Artists

Uurintuya Dagvasambuu (b.1979) is a Mongolian contemporary master of the traditional painting, Mongol Zurag. She is known for innovations in this style: she combines traditional Mongolian and Buddhists motifs with contemporary themes as she chronicles the lives of women, mundane everyday life, seasons of life in her post-nomadic homeland. Uurintuya trained at the Institute of Fine Arts, Mongolian University of Arts and Culture. She began exhibiting while a student since 2001 and had solo exhibitions in Ulaanbaatar in 2006 and in 2018. Uurintuya participates in Mongolian Art group exhibitions at home and internationally, which include Las Vegas (2006), Beijing (2008), Hong Kong (2011), Shanghai (2012), Fukuoka, Japan (2012, 2014), London (2012), Düsseldorf (2012), and Queensland, Australia (2015). Uurintuya’s development of traditional motifs, subject matter and pictorial language into unique representations of Mongolian contemporary quotidian has been recognized in Mongolia as her works were often selected as the winners of “The Best Work of the Year” prestigious awards bestowed by the Union of Mongolian Artists annually to only a few artists.

Baasanjav Choijiljav(b. 1977) is a Mongolian contemporary artist known for his important contributions to the development of the traditional style painting Mongol Zurag. He was trained at the Institute of Fine Arts, Mongolian University of Arts and Culture in 2000-2005. His solo exhibitions began in 2006 with the works that dwelled on the topics of Mongolian history. Baasanjav has pioneered the usage of the traditional motifs outside of their original context and iconographic meaning for addressing political and environmental issues of Mongolia’s neoliberalism. He has shown in Mongolia and internationally since 2005: Hong Kong (2011), Shanghai (2012), Ukraine (2011), London (2012), South Korea (2015). His solo exhibitions were shown at Fukuoka Asian Art Museum in Japan (2013), Barcelona (2007), Gwangju, South Korea (2018) and his native Ulaanbaatar (2006, 2019).

About Curator

Uranchimeg Tsultemin, Ph.D. specializes in art of Mongolia and Tibet. As an Assistant Professor at the Mongolian University of Arts and Culture (1995-2002), she has curated Mongolian art exhibitions internationally: Tsukuba, Japan (1997), New York, NY (2000), Bonn, Germany (2001), Hong Kong (2011), Shanghai (2012), and two exhibitions at Venice Biennale in 2015 and Ulaanbaatar (2018). She published widely on Mongolian Art. She received her Ph.D. in History of Art from UC Berkeley in 2009 with the dissertation on Mongolian Buddhist art of the 17th - early 20th c. titled "Ikh Khüree: A Nomadic Monastery and the Later Buddhist Art of Mongolia."Recently she served as a Lecturer at the Department of History of Art at UC Berkeley, a Visiting Associate Professor at National University of Mongolia, also as the John W. Kluge Postdoctoral Scholar at Library of Congress. In 2014-15, she is working on Mongolian Buddhist art and texts funded by the American Council of Learned Societies. Dr. Tsultemin is currently the Edgar and Dorothy Fehnel Chair of International Studies and Assistant Professor of Asian Art at Herron School of Art and Design, Indiana University.

[1]See more in detail about the history of Mongol Zurag in Uranchimeg Tsultemin, “Mongol Zurag: Nyam-Osoryn Tsultem (1923-2001) and Traditional-style Painting in Mongolia” in Orientations, 48/2, March-April 2017, Hong Kong, pp. 135-142.

[2]For Urga, see Krisztina Teleki, Monasteries and Temples of Bogdin Khüree1651-11924 (Ulaanbaatar: Institute of History and Archeology, 2011); Uranchimeg Tsultemin, A Monastery on the Move: Art and Politics in Later Buddhist Mongolia(Honolulu: Hawaii University Press, fall 2020).

[3]On these East Asian traditions, see Julia Andrews “Traditional Painting in New China: Guohuaand the Anti-Rightist Campaign,” in Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 49, no. 3 (Aug.1990), 555-585, Andrews, Painters and Politics in the People's Republic of China, 1949-1979 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), Ellen P. Conant, Nihonga, Transcending the Past: Japanese-Style Painting, 1868–1968(The Saint Louis Art Museum and The Japan Foundation, 1995).

[4]See, for instance, Bert Winther-Tamaki, “Yōga: The Western Painting, National Painting, and Global Painting of Japan” in Review of Japanese Culture and Society, Vol. 25, Working Words: New Approaches to Japanese Studies (December 2013), 127-136.

[5]Nyam-Osoryn Tsultem also published several books on Mongol Zurag, such asHistory of Mongol Zurag from Ancient Times(Ulaanbaatar: The Union of Mongolian Artists, 1988), Tsultem, Development of the Mongolian National Style Painting ‘Mongol Zurag’ in Brief(Ulaanbaatar, Gosizdatel’stvo, 1986).

[6]See a detailed analysis of this painting in Uranchimeg Tsultemin, “Cartographic Anxieties in Mongolia: The Bogda Khan’s Picture-Map” inCross Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review(Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, December 2016 (online issue), May 2017 (hard copy), 66-87.